In this short guide, we’ll tell you what will be helpful, and, just as importantly, what you definitely don’t need to get started with birdwatching in your nearest outdoor space. We’ll also give you a few examples of the birds you’re most likely to see in a British garden and a few birds that you might be lucky enough to see. And maybe even a few that you’ll be extremely lucky to see as well. We all like a challenge.

The first and most important thing to say about birdwatching is that you don’t need a garden. You can, of course, do it by watching some well-established garden birdfeeders, but it can just as easily be a local park, your balcony, or by sitting watching the tree on the street outside your kitchen window. Naturally, a garden, terrace or balcony is a great place to sit and do a bit of birdwatching but, honestly, wherever you’ve noticed birds in the past is as good a place as any. What really matters is the quiet joy of spotting something, identifying it, and enjoying a moment of private triumph – especially on the magical occasion when you spot something you haven’t seen before. There is genuinely, in our opinion, nothing like it.

The second thing to say is that you don’t need any fancy equipment either. Binoculars can help identify birds with a bit more accuracy but broadly speaking, the true pleasure of garden birdwatching is in the glimpses, the flashes, the ‘I think that was a…’ moments. The more you’re actively on the look out for birds, the more you’ll learn to identify them from flashes of colour, from noises, and even from their location. Small brown bird in the undergrowth? Probably a wren. Solitary bird singing merrily at around head height? Likely a robin. Flock of chirruping, twittering small birds right at the top of a tree? Almost certainly goldfinches. For the pure satisfaction of owning one, a bird book is always nice but there are plenty of ways to accurately identify birds nowadays…

Things it doesn’t hurt to have:

- If you like the idea of a bird book (they are nice, to be fair) then you could do a lot worse than the RSPB’s Handbook of British Birds. It’s in its fifth edition now, comes with beautiful illustrations that are very helpful when identifying birds by their plumage and fits neatly into a pocket. You can buy the current version from the RSPB and I have never known a second hand book shop to not have at least one old copy in stock.

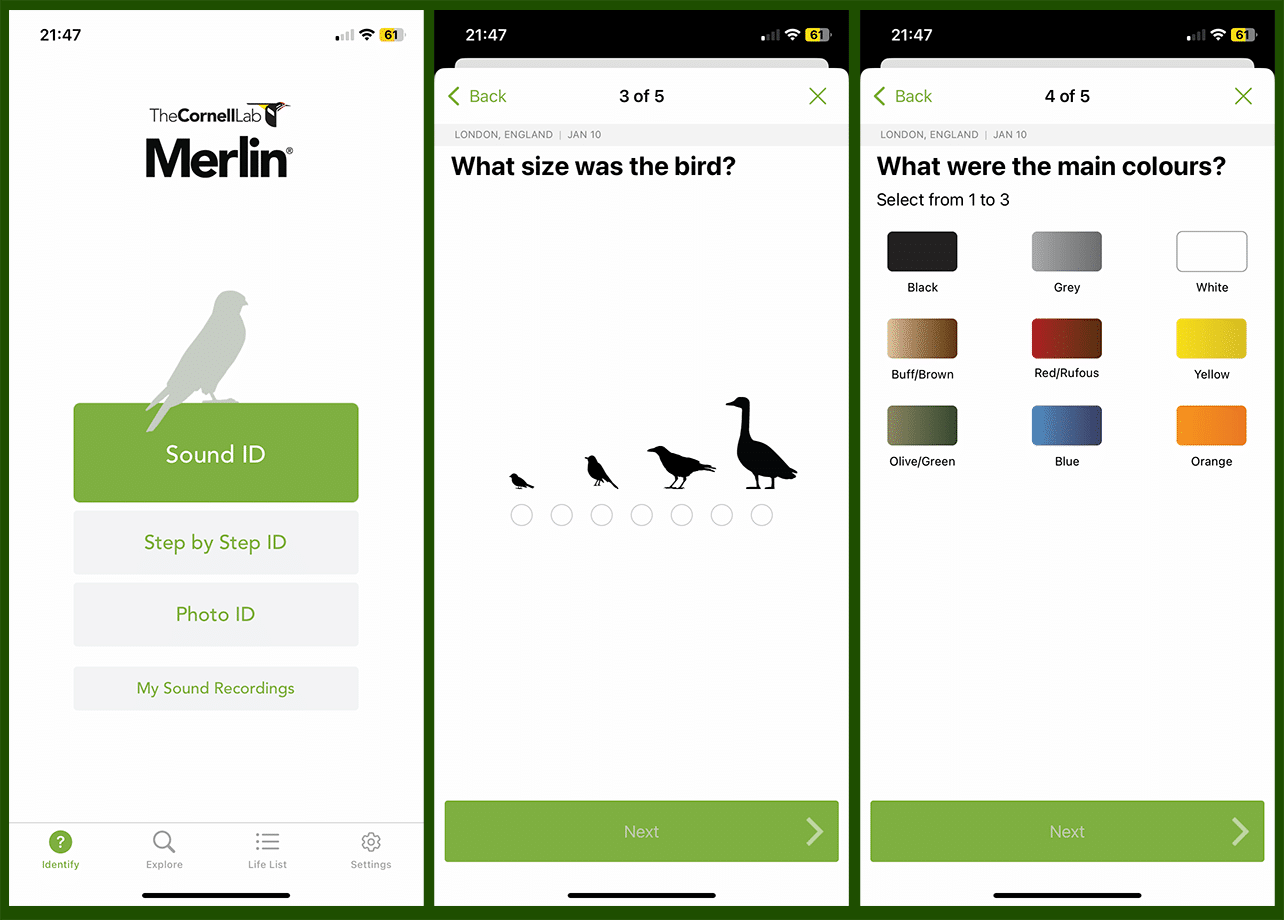

- Alternatively, Cornell Lab’s Merlin Bird ID app is a brilliant bit of technology. It allows you to identify birds through either recording their singing on your phone, by uploading a photograph, or by a step-by-step process-of-elimination questionnaire about what the bird you’re trying to identify looks like, what it’s doing, and where you’ve seen it. It’s never let us down.

- Though you don’t really need them, a notebook and pen or pencil is a nice way of recording your sightings too. If you’re taking part in the Big Garden Birdwatch then it’s important to write down what you see as you go.

If you’re interested in taking part in the Big Garden Birdwatch, there’s still plenty of time to sign up. Simply visit the RSPB’s website and register for a free digital or paper pack to help you identify and note down your sightings over an hour on the weekend of the 26-28 January. There’s lots more information on the RSPB’s website but, in the meantime, here’s a glimpse of what you might see:

A familiar sight, the House Sparrow (passer domesticus), is a regular in British gardens – though numbers are sadly, like many other species, on the decline.

These gallumphing great things are Wood Pigeons (Columba palumbus). One of the more comedic garden birds in our opinion and always a joy to watch.

The Great Tit (Parus major) is easily identifiable by its black-striped, yellow breast and a call that sounds a lot like ‘Teacher, teacher’ over and over.

A flock of Goldfinches (Carduelis carduelis) is very pleasingly known as a ‘charm’. They travel in groups and can often be spotted gathering at the tops of trees.

A very common sight in our gardens, but no less worthy of our attention for their beautifully subtle plumage, this is a Blue Tit (Cyanistes Caeruleus).

Sometimes easy to confuse with a Great Tit, at a distance, the Coal Tit (Periparus ater) is distinguishable by its much smaller size and lack of yellow breast.

Common Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) move about in large, rowdy gangs – chittering and chattering. Underratedly spectacular birds in our opinion. If you’re lucky you’ll see hundreds of them gathered in breathtaking murmurations at this time of year:

A murmuration of Common Starlings

The blue and orange of a beautiful Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs).

An under-rated, and often overlooked garden bird, the closer you get to a Dunnock (Prunella modularis), the more beautiful you’ll notice they are. Sort of the opposite to an oil painting.

Ever-present, always singing their hearts out, the Blackbird (Turdus merula) is a mainstay in most UK gardens. (This one’s a male. Females come in a very fetching brown.)

The gardener’s friend, as well as immensely territorial and solitary birds, Robins (Erithacus rubecula) are bold, bright, inquisitive and make excellent gardening companions.

Woodpeckers, such as this Green Woodpecker (Picus viridis) are rare sights, but not endangered. They are shy, so when you catch a glimpse of one, it’s always a pleasant surprise. Fun fact about woodpeckers: they are able to wrap their extremely long tongues around their brains to protect them when hammering against a tree. Baffling stuff.

Described by the artist Matt Blease, (whose bird illustrations are really great for children), as ‘tiny clouds in tracksuits’ the Long-Tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus) is a relatively uncommon sighting – not least because they tend to move around a lot, unhelpfully. They travel in groups, and flit rapidly from tree to bush to tree. Worth keeping an eye out!